In Conversation with Koushik Banerjea, author of Another Kind of Concrete.

Q1 How did you get into writing? What inspired you to write Another Kind of Concrete?

My love of writing goes back all the way to being a little kid who adored reading. I was lucky, in that my Mum always encouraged me to read, from very young, say from the age of about 4 or 5, which was just as well, as there was precious little of that going on in my school at that time. But I loved the absorption of reading, even how the letters looked on the page, could almost see them coming alive in front of me, warping under a magnifying glass. So I suppose you could say I was a sensual reader, even before I fully understood what all the words meant. Books, reading and libraries were always magical, meditative spaces for me, product and method combined in a thrilling, immersive form. And even if it sounds a bit weird, I liked the way certain words just looked, or tasted on the tongue. So many stories tucked away in those pages, virtually all of them more appealing than anything in my average school day. Which is when I started making things up, and finding out that it was a lot of fun, even if it occasionally got me into bother. I think I started telling tales because I was bored in class, and my mind was constantly wandering. As I got older, the temptation to put some of them down on paper became irresistible, and of course my understanding of the words themselves, and their functional, as well as mythic properties, began to spill over into more serious attempts to write.

As regards Another Kind of Concrete, whilst elements of it have doubtless been gestating in my head for decades, the catalyst for writing it was actually a tough moment for me personally. I’d just taken my Dad’s ashes back to India, and had the strongest feeling that I owed his playful, occasionally wayward spirit, something more than filial duty. A story of some kind, which offered a canvas for that spirit, and for all those other pioneering immigrant souls, seldom remembered, to speak the unspoken. I was very down at that point. I’d lost my father, was out of work, and my prospects looked grim. What better moment than that to start!

Q2 Can you tell us a little bit about Another Kind of Concrete?

The story itself rippled outwards from a stray remark by a friend of mine, who offered the phrase as a description of our physical surroundings on a night out some years back. I think he was being philosophical, which often happens several sherberts (beers) in, but the comment stayed with me, put me in mind of other concrete monstrosities I’ve been around, as well as of the idea that, as with freshly laid cement, there’s still a moment to make your mark before the pattern sets. Which struck me in a strange way as a little bit like the outlook of many immigrants, and their kids, or really of anyone on the make in a strange, often hostile environment. We’re all looking to make our mark before things are set in stone, be that through official or unofficial channels. So that was the energy, the ethos if you like, that became the spine of a much bigger story. On one level, it’s a coming of age tale, about a very young boy growing up, perhaps too fast, within the accelerated ruins of 1970s London. He’s witness to, and participant in, the tumultuous histories unfolding around him – punk, social collapse, vicious racism – and at the same time he’s just a young kid who loves cricket, books, and messing about with girls in the library. Again, rippling out, is a phantom history of post-war London, from Windrush (1948) to the Battle of Lewisham (1977), and the boy’s family, caught in the crossfire, is battling its own demons left over from the Partition of India (1947). So this is also a tale of refugees remaking their own lives, and that of the city they have found themselves in – London. The empire strikes back, so to speak, amidst the white heat of working class London and its many tribes: skinheads, punk, reggae. It stitches together its own thread from the crumbling remnants of the past, but lives intensely in the present. Histories, people, style, music – all are on the make in this story. A tale of something from nothing. Immigrant ingenuity, the true essence of punk.

Q3 What does your writing process look like?

Some bits never change. There’s an awful lot of reading, random note taking, thinking, which often reaches a pitch just before the actual writing starts. An extended preamble full of argument and confusion. But then something seems to happen, some alchemy that starts transforming the words, jottings, thoughts, ideas, into another form. Longer sentences, paragraphs, and onwards. Truth be told, I didn’t plan all that much of the novel, it just started to write itself after a while. The key seemed to lie in a certain discipline – getting up very early in the morning and putting in a couple of hours (as I was doing other work during the day), and then returning to those words later. After a while, momentum started to build. Instinct kicked in, the words suggested themselves, and the rhythm, tone, texture, voice, all started to become clearer. In an odd way it was as though the words themselves knew whether or not they were the right ones. I think the tonal quality is apparent to the author even before it secures its berth as narrative fact. As with music, you just know when you’ve hit a dud note. But it’s after you let go, submit to the idea that the story you thought you were telling isn’t necessarily the one you end up with, that the process, in my case at least, picks up steam. This is that beautiful ‘state of grace’ that other writers have described, whereby tone, texture, narrative all begin to chart their own course. The real story within. Highly welcome too, given that I’d tripped and fallen on the page a hundred times before the words themselves decided to help me out. I suspect the feeling of inadequacy, of needing to ‘fail better’, is a vital part of cutting one’s teeth, so to speak, though of course there’s probably as many different kinds of apprenticeship as there are ways of learning how to be a writer.

Q4 What do you find most difficult about writing?

It’s different things at different times. One moment it’ll be vagaries of plot, character, rationale, when a key protagonist has been found slumped in a local hostelry for no good reason. The next it’s motivation, whether that’s the temptation to kill him off for being such an unlikeable soak, or the sense that the tale itself is meandering, much like life can, into a cul-de-sac of its own making. I often make a couple of false starts which tend to rehearse some of these doubts, and while it’s frustrating to have to junk a project having already expended a certain amount of time and effort, it does make it easier to spot when the words, like those musical notes, feel right. Writing can be a solitary activity, and whilst there are unique pleasures to be had in one’s own literary company, for instance little discoveries around form, or subtext, there’s a downside too. It can get lonely. It’s tough trying to stay motivated if you feel you’re pitching into a void, or trying to maintain your self-belief as a writer through the endless carousel of rejections. Tricky too if you don’t feel your work is necessarily valued or supported in the wider world, perhaps even by your own publisher! Keeping going under such circumstances becomes a sheer act of willpower. But the truth is, even if all the above were moot, you’d still have days when you’d get writers’ block, feel hopeless, and wonder why on earth you ever set out on this route in the first place. In the past I’ve always done other jobs, so luckily haven’t had to rely exclusively on writing to pay the bills, and to be honest, that’s the case, I think, for most writers. But the harsh reality is, you’ve gotta pay the bills. Writing under the stars is only romantic if there’s somewhere else you can go once the seasons change and it starts tipping it down.

Q5 What lasting effects have your favourite authors had on your writing and style?

If there’s any truth to the adage that literature is a quarrel with and about the world, then the business of encountering authors who inspire in some way is probably as much about technique as it is aspiration. If you’re going to have a row with the world, probably best to come prepared. A good defence, or jab, might not be enough. Chances are you’re going to need whatever the literary equivalent of a gazelle hook is too. At any rate, that’s been my approach to literature for some time now, enjoying other writers’ work in one reading, perhaps studying the form in another, trying to figure out why certain sentences, or stories, are so impactful, while others fall flat. It’s no surprise then that over time I’ve built up something of a mental inventory as to who is particularly good at what. And this is also really helpful, I’ve found, in resolving certain difficulties which might arise for me on the page. 'How would Clarice, or Hanif, go about this?' is a useful thought to have when stuck, for example, on questions of form, narrative function, emotional resonance. I suppose in that way the inventory’s a bit like a list of approved tradespeople in the phone book, though some writers can get a bit precious about the nuts and bolts of what they do. Luckily that’s not one of my afflictions, as I love those Paris Review ‘Art of Fiction’ interviews, which have been attempting to unpick the secrets of great writing, and great writers, for a century now. Anyway, long story short, I’d hope my own work reflected, in its brighter moments, some of those inspirations, as well as having something interesting of its own, and of literary value, to say about the world. That list though would have to include: Clarice Lispector and Hanif Kureishi; Sam Selvon, Percival Everett, Viet Thanh Nguyen; Elena Ferrante, Rachel Kushner, Edwidge Danticat; Marlon James, Jhumpa Lahiri, Yuri Herrera; Salman Rushdie, Paul Beatty, Mohsin Hamid; Lucia Berlin, Roberto Bolaño, Tommy Orange; Hiromi Kawakami, Haruki Murakami, Fuminori Nakamura; Cristina Rivera Garza, Rumi, John Fante, Charles Bukowski. Perhaps it’s delusional, but I’d love to think, if only by craven osmosis, that some of the good stuff has rubbed off on me and is there in the form, the words, the desire.

Q6 As a former academic in postcolonial theory, what are three of the most important themes we can expect to find in your story?

There’s relatively few academics who make the leap from academia into fiction, though of course there are many writers who head in the opposite direction, occupying teaching positions and perhaps enjoying the financial security of an institutional base. In my case, I think academia must have been the blockage in the pipes, as, it’s only in the intervening years since I left academia that my writing seems to have flourished. My reading too, as I’ve devoured more, and produced more, over the past decade than at any time when I was working in academia. They’re very different disciplines, and I seem to have returned to what I first did all those decades back, when I was sitting bored in class. Telling tales is always where, and how, I was happiest. Postcolonial theory, in as much as it attempts to make sense of a world scarred by the degradations of colonialism and Empire, is doubtless present in the novel, albeit at a purely thematic level. But it’s certainly one way of foregrounding the much bigger, and ongoing, stories of Refugees, Displacement, and their reinvention as the quintessential figures of the modern postcolonial city, in this case London.

Q7 What do you do when you’re not writing?

As you’ve probably worked out by now, I do love to read. I’ve got a sizeable backlog that’s built up over time, and I’ve been working my way through this during spare moments. It can be hard finding the time though as I’m a primary carer, so a great deal of my day is taken up by that. It certainly helps focus the mind though, knowing that there are only limited opportunities in any given 24-hour period to read, or write for that matter. So I’ve tried to be as disciplined as possible in how I go about things. Simple pleasures too have been important over this time, and throughout lockdown. I’ve really come to appreciate even a spare hour just to go for a walk, reacquaint myself with some birdsong, or breeze. On those walks I find I’m often drawn towards cats, left with the feeling that while they may be acting nonchalant, they’re actually studying us minutely. Nature, including the ostensibly mundane kind I’m describing, is often the part of my day I most look forward to. That, and tea, which I almost certainly drink too much of. Something else that I’ve found myself doing increasingly is revisiting a mountain of old cassettes (I know, I know). It’s been fascinating hearing old mixtapes, pitching myself right back into that time and place, those memories which spool out with the sounds. A great way of travelling too, without ever needing to worry about visas or quarantine.

Q8 Another Kind of Concrete is published with Jacaranda Books, what was that process like? Did you originally intend to publish your book with an independent press? If so, why?

The process wasn't quite what I had anticipated. I was unlucky to be met with a double-whammy of unfortunate timing - my book was published just as the Covid situation was coming to the fore and the lockdowns that followed meant that in-person events (book readings, signings, talks) to promote my novel weren't possible. On top of that, although my publisher was resourceful and strategic enough to schedule online publicity events and other marketing opportunities for several of its other authors, my book was released during a year when their focus was on a particular campaign which my own work didn't form a part of. As such, this debut, which is very close to my heart, didn't receive a 'launch' of any kind upon its publication, and there has been no real communication from the publisher since.

I didn't honestly have any specific expectations regarding the type of press my book would be published with. As it was my first novel and I approached the publishing world without having any existing contacts in place, my aim was simply to have my book published and to get this story out there, especially as there are characters whose substantive experiences and histories I hadn't previously seen chronicled elsewhere.

Q9 The main character in Another Kind of Concrete is one of the London-born children of immigrants who moved to the UK after the Partition of India. Can you tell us how important diversity is on readers’ bookshelves and why original voices/stories like yours are important today?

Reading widely and having a wide range of books to choose from are more often than not indicative of a healthy curiosity about the wider world and a keen appetite for adventure, even if it’s only limited to the page. Art, as they say, can set you free, and so it is, I think, with literature. Books, words, the absorptive quality of reading, can all help orientate the reader to a wider public realm, including an unfamiliar one, and in a way which broaches curiosity, not fear; enjoyment rather than hostility. Stories, after all, have the potential to say the unsayable, or introduce the unknown. Unfamiliar characters, cultures, experiences permeate the reader’s consciousness, but as art rather than threat. Which is probably why all manner of autocratic regimes have historically gone in for book burnings, censorship, outright vilification of ‘non-prescribed’ texts. Stories tell us something about ourselves, our foundational myths, and all the hubris and narcissism that comes with. But their deeper value is in their potential for offering other ways of looking at or of being in the world. It’s a bit like the classic Kurosawa film, Rashomon. We’re probably all grappling with the same event – how to live, love, be – and serious literature, beyond its intrinsic pleasures, affords us multiple viewpoints, which can be both useful and thrilling. This is my understanding of ‘diversity’, and it belongs to the same philosophical impulse which senses that one’s presence in this world is enriched by having empathy, more so when that’s with people or events that aren’t necessarily familiar. Diverse literature, distinct voices, and the interconnectedness of reading and a particular type of being are all welcome elements in this equation. More curiosity equals less fear, and that in turn manifests in less Farage. So a good thing all round really.

Q10 What are you reading at the moment?

As previously mentioned, I’ve been making inroads into a fairly wide-ranging backlog. I tend to have more than one book on the go at any given moment (probably a result of all that caffeine from all those cups of tea!). Anyway, current reading includes Rumi – ‘Selected Poems’; James Baldwin – ‘The Cross of Redemption’; Elena Ferrante – ‘The Lying Life of Adults’; Ayad Akhtar – ‘Homeland Elegies’. Also, an amazing and rather beautiful memoir by Suresh Singh – ‘Memoirs of a Cockney Sikh’.

Q11 What's the most useful advice you could give to an aspiring author?

Read widely, be disciplined and take the writing process seriously, but enjoy it and believe in yourself. Don't be too disheartened by any setbacks - sometimes life gets in the way, so you might not always be able to write when you want to. Also, find the method that works for you - some people need complete solitude to write, others don't. Some writers are at their best first thing in the morning, others are night owls. There is an analogy here, I think, with the sophisticated system of producing and arranging sound in Indian classical music. There are specific arrangements which correspond to particular times of the day. Hence, morning raags, afternoon raags, and evening raags. As a writer you just need to figure out which one you are, and then make that part of your ‘method’. Perhaps most of all, keep in mind why you are writing, which hopefully has something to do with a love of language and stories, and because writing brings you joy and satisfaction. You might also have a particular story to tell. This will help to get you through any difficult times.

Q12 There are many cultural references and touchstones in this novel, particularly when it comes to music and also characters' attire. Has music played an important role in your life and would you describe yourself as a 'fashionista'?!

Haha! Much as I might like to think of myself as a sartorialist, I’ve more often been described in other, less flattering ways! But you’re right, music and threads do feature throughout the novel, and they matter. Again, it’s something to do with how we appoint ourselves when facing out at that wider world. The rakish angle of a trilby, sharp-suited Mods, rude boy style or even the groans from the reggae-loving regulars whenever soulboys would turn up at their various shindigs. If you grow up in south London, you’re never far from music of some kind, so it’s probably lodged in your consciousness whether you like it or not. As it goes, I used to love the pirate radio stations broadcasting underground soul, funk, reggae, and then later jungle. All out of the high rises with the brio that only true rebels possess. Sound systems and house parties were a regular feature of that time when I still had the energy…and the hair! But really I’ve always loved music, ever since my Mum got me my first record, way back in about 1975. It was a mint 7” vinyl pressing of ‘The Bare Necessities’ (from The Jungle Book). She bought it in the foyer of the Lewisham Odeon, our local cinema, where they were selling merch from the film. I’ve still got it, it’s still mint, and I even used to occasionally play it while DJ-ing, back in a different life, the one where I had the hair and the energy. And as for the other bit, well, who doesn’t like threads? A tasty whistle (suit), or some bespoke high waisters evoking their own memories of something sublime. Sounds, shapeshifting and sheer joy. Baloo the bear loves music as well, and he knew a thing or two about having style. As I might have already mentioned in passing, these days it’s old cassette mixtapes that have really got their hooks back into me and got me time travelling. Music and style, I suppose they’re the first foreign languages we properly learn. And learn to love. And that’s that really. On good days I think I can hear a rhythm and a cadence in my words, but those are probably also the days when I’m convinced that I’m not actually a scruff. A fella’s gotta dream…

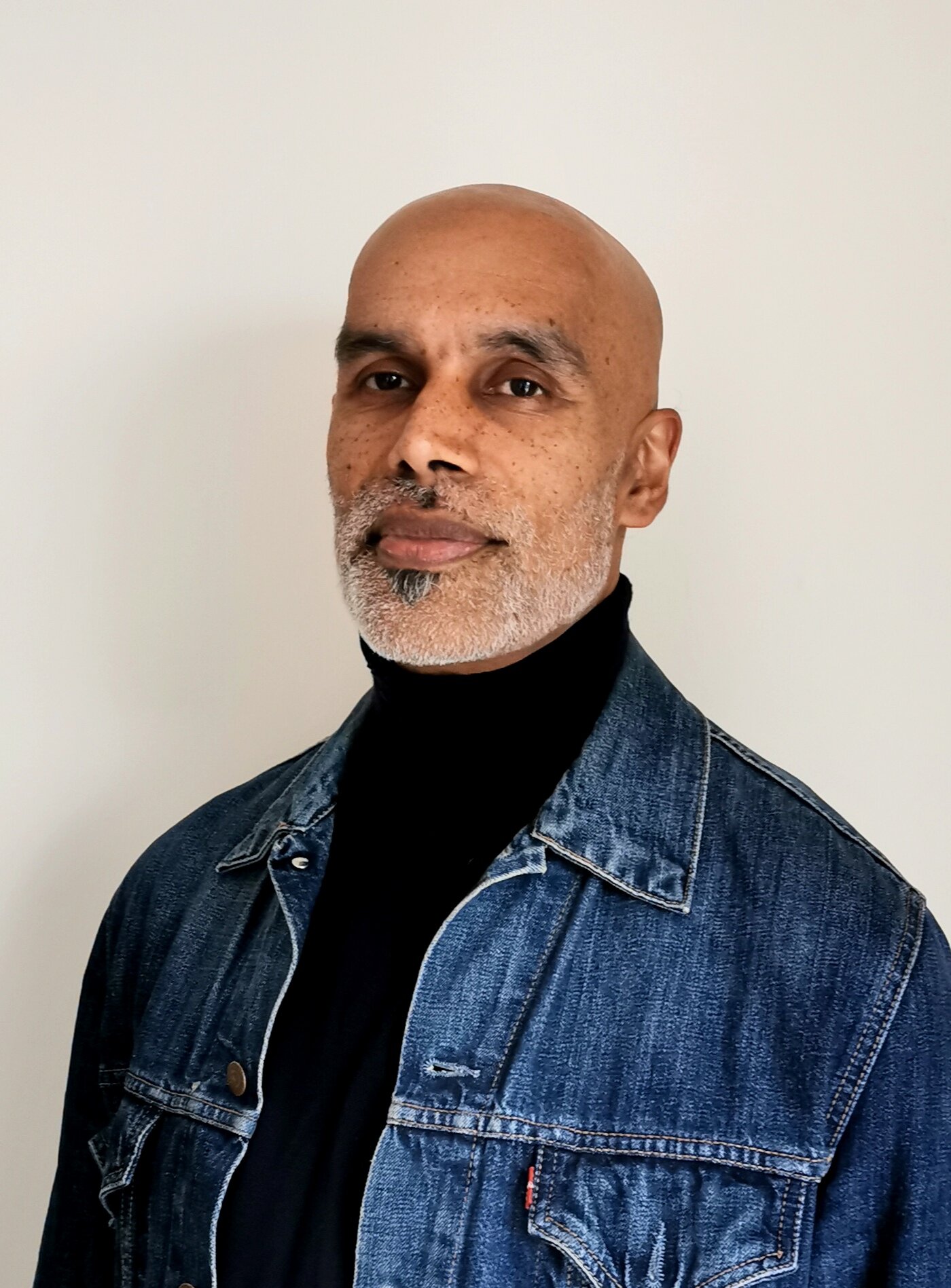

About the Author

Koushik Banerjea is a regular contributor to ‘Verbal’. His short fiction has also appeared in writersresist.com, minorliteratures.com/ and his journalism in 3ammagazine.com/3am/. Another Kind of Concrete, published during lockdown, is his debut novel. In a former life, he taught postcolonial theory at the London School of Economics, worked as a feature writer on the cult journal, 2nd Generation magazine, and DJ’d as one half of ’The Shirley Crabtree Experience’. He is also a lifelong book addict and a long-suffering West Ham United supporter.

Author website

Contact

Social Media

Instagram @hark.athim

Book title

Another Kind of Concrete

Publisher

Jacaranda Books

Synopsis

Pet rocks, flares, ABBA and kitsch. Well this isn’t that seventies. These are years of drought and disaster. IRA bombs, Indian batting collapses and bricks flying through immigrant windows in London. But once the glass has been cleared up and the cops have had their say, there’s still a kid inside who’s interested in doing his nightly spelling tests. He’s freshly divorced from his hair following a recent trip to India, and if that’s not bad enough, the man responsible for scalping him did so in broad daylight with the full blessing of his own parents. However the real violence still awaits back in London, the concrete and the inhabitants starting to

crack up as yet another heatwave takes hold. Or perhaps it’s an even older story, long since woven into the fabric of lives shattered by the Partition of India and then put back together, piece by piece, in the old engine room of Empire - London - where debts are called in and crime is rarely followed by punishment. Even with his freshly shaved head, K., the kid with the spelling tests, is no skinhead. His stomping ground is that other 1970s, the one that rises up out of the cracks. Cockney rebels, sex fiends and a strange new sound they’re calling ‘punk’. This

England was dreaming. Then one day it awoke. Festooned with streamers and safety pins, nursing a long, triumphalist hangover while in its shadows something primal has begun to stir. The cracks are widening and this time it seems as if the lies of the Jubilee will be swallowed up by the abyss. It’s another long, hot summer south of the river and the tribes are getting restless… The surreal world of an inner-city boffin. Just below the surface, and sometimes not even that far, Another Kind of Concrete.

Book extract (pp 383/384)

The cold seems to scythe straight through his coat. He is barely out of the house and already he can feel it piercing through to his chest. In the playground predictably enough there they all are, T shirts and the occasional jumper but nothing else to even remotely suggest this is winter.

The girls at least are huddled in little groups, occasionally looking over at where the big game of football is going on, but very few of them are wearing coats either. One of the nasty girls from his class, Lisa, is pointing towards the library. She shares a joke with the rest of her group and they all laugh.

There, outside the building he knows so well, is Rachael, sucking her thumb and looking like the one person here other than himself who is actually shivering.

‘Hallo.’

It is Michelle. She has crept up behind him, putting her hands over his eyes. Feigning ignorance, he goes, ‘Denise?’

‘No, silly. It’s me!’

‘Oh, is it? I thought it was Denise,’ he pretends, hoping she hasn’t picked up on the gratitude in his voice.

‘You’re silly,’ she tells him, slipping her hand into his, the manoeuvre well disguised by the ample cloth of her duffel coat.

Perhaps it is because they are so wrapped up in each other’s relief, that neither of them notices the little pair of snake eyes wandering from the big game to the perimeter fence, settling on a spot just beyond the cloth and whatever it is that they truly covet.